Freedom to Lead International® (FTL) provides leadership development services to leaders in 50 countries throughout South Asia, Africa, and North America. We specialize using methodologies that engage leaders who are more likely to be influenced through oral-based methods (stories, images, drama, poetry, music, etc.) rather than through abstract theory or concepts. We call these people “storycentric communicators.”

This video outlines some of the secular research, science, and cultural anecdotes behind this story-based methodology for adult learning. It challenges people in western cultures to realize the power of story, perhaps seeing that this story-based approach is for all of us.

Transcript:

The Power of Storytelling

(Rick Sessoms:) Freedom to Lead International® is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit entity that provides leadership development services to leaders in South Asia, across Africa, and in the US. We specialize in using methodologies that engage leaders who prefer and are more likely to be influenced through oral-based methods rather than through abstract theory or concepts. We call these people “storycentric communicators.” The oral-based tools we use include stories, images, drama, dance, poetry, and music. We call these methods the “storycentric arts.”

Think about a story you’ve heard that had an impact on you. Why did that story impact you?

Several years ago, my wife and I visited Broadway to see the musical Wicked. This show is a prequel to The Wizard of Oz. It tells the story of Elphaba, the Wicked Witch of the West, and her early history in the land of Oz. Elphaba was born with an unnatural shade of green skin, so she is misunderstood and ostracized. When she goes off to school, she ends up rooming with the popular Galinda, later to become The Good Witch. Galinda inspires Elphaba to travel to the Emerald City to meet the Wizard. Elphaba’s only desire is to work with the Wizard, the Great and Powerful Oz. Of course, as we already know, the Wizard is not so great and powerful. He is, in fact, a fraud who turns out to be the most insidious sort of evil there is.

The matinee show we attended was packed. The story and the music were superb, and the message was riveting, filled with life lessons. Yet no one stood up at the end and said, “There are four points you ought to learn and should apply.” Tina and I left with just the story stirring in our hearts and minds. We went to Starbucks and discussed it over coffee.

Could it be that good and evil are often perceptions? Is true goodness found in being true to yourself? What is the potential cost of turning from worldly power to pursue a nobler path? All powerful lessons about integrity and truth and authenticity and reconciliation. All from a musical. From a story.

The Power of Storytelling at Amazon

Many of today’s most influential institutions are turning to story – Broadway, television, movies, the news media, business leaders. Two years ago, Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and CEO, banned the use of Power Point in Amazon’s executive meetings. He now requires his senior team members to communicate with one another through “narrative memos.” So when they come together for meetings, his colleagues read silently one another’s memos that are structured in the form of stories. After everyone’s done reading, they discuss the topic.

Bezos and some of the world’s most inspiring entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and Richard Branson are confirming what neuroscientists have known for centuries. Our brains are hardwired for story, not for lists. We recall and retain information more effectively when it is presented in the form of stories and images rather than bullet points on a screen. Stories touch our lives and call us to action.

Over the past forty years, I’ve spoken to many different kinds of groups in diverse settings on a variety of topics. But regardless the group or the topic, one kind of feedback has been consistent. I can’t count the number of times someone has said, “I remember that story you told. Don’t remember much else, but I remember the story.”

Biases Against the Power of Storytelling

(Michelle:) Even though stories impact us, there are some biases against story that prevent some from thinking about story as a viable means of communicating important principles to adults. Story for these people suffers from a tarnished reputation.

1. For starters, they view story as a device used to put a spin on something.

Story is a ploy to stretch logic, certainly not a vehicle to convey important truth. So viewing it from this angle, the very word “story” is a negative word. It means untrue.

And I understand this bias. As a child, I would say to my grandmother, “I must have lost the change. It was in my pocket when I left the store.” To which she would say, “Now don’t you tell me a . . . story.” With this negative view of story, some doubt that story can be a reliable vehicle to convey truth.

We tend to grasp the meaning of words by defining them in association to their opposite. For example, the word “hot” takes on additional meaning when compared to “cold”. More meaning is given to “high” when compared to “low”. Compared to “poor”, the word “rich” takes on relative meaning. But the English language has no antonym – no opposite – for story – except for “non-story”. As such, story is then related to other similar comparisons: fiction versus nonfiction; truth versus non-truth; real versus unreal. Thus, story is often equated with make-believe, with unreality, with fiction.

Just as my grandmother thought that my “losing the change” was just a “story,” people often relegate the term “story” to communication of that which is not true. The comment is heard from the boardroom to the halls of Congress: “Why didn’t he just tell us the facts?” “Is he trying to cover up something with a story?” With this assumption, it’s understandable that academia and the church tend to shy away from depending on story to communicate serious lessons.

In addition to story being relegated to the category of untrue, there’s another bias against story.

2. It’s the bias that stories are for children.

Therefore, they’re lightweight. You and I were introduced to stories as children. These childhood stories we heard were designed to entertain and to educate. However, as we grow up, we’re taught to put away these childish things. We were encouraged to grow out of the story realm and enter the adult world of non-story facts.

For many adults – especially in western culture – story just doesn’t seem serious enough to convey important information. When a listener evaluates the speaker and says, “Well, he told some good stories,” it is often another way of saying, “There was no substance to it.”

3. In addition, institutions of higher learning have created a prejudice in us against story.

Remember college? We prepared papers and reports that were graded on their analytical content. In the classroom, story is usually considered fringe, embroidery, decorative edge. So when the professor wants to provide students some rest from taking notes, the prof might tell a story. But when the information she wants to relay is really important, the teacher tends to dismisses the story—it might be interesting, but it cannot carry the freight after all—and she reverts to concepts abandons the story, and replaces it with four points. Appropriate application has its place, yet many educators and pastors never quite get the point when somebody says, “You know, I remember that story you told.”

What do we mean when we talk about story?

In light of these biases, let me clarify then that when we talk about “story,” we are referring to a communication structure for content that may be true or false, fact or fiction.

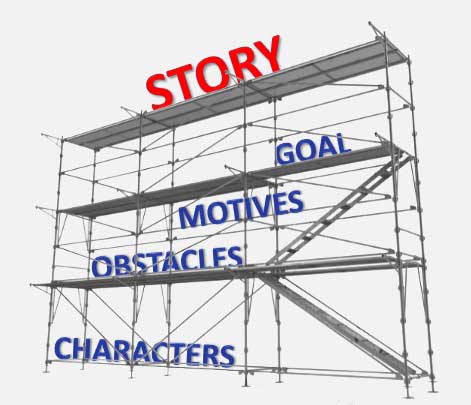

Story is simply a ”scaffolding” upon which any content can be built for the sake of learning and meaning. Good stories feature characters that face external obstacles as well as their own internal motives in the journey toward a challenging goal. Events in an effective story don’t happen for their own sake, but to demonstrate real human struggle. Story can carry higher levels of learning. It can create context for complex ideas and information to be passed on.

No matter how much education we have, no matter how old we are, great stories move us. They connect us. They change us. Stories told well are not just decorative embroidery. In fact, for storycentric communicators, story doesn’t just illustrate truth; story actually carries truth.

(Rick:)

The Dark Side of Literacy

Alongside our emphasis on the importance of story, I want to make a disclaimer: I am a passionate champion for literacy. I have spent most of my career in books and abstract theory. It would be dishonest not to advocate for the benefits that literacy and education have brought to my life.

But there is a dark side. If pushed too far, literacy with its focus on the intellect has a tendency to diminish the perceived value of our emotions as pesky distractions.

Recent research shows that literacy can push us to overuse one hemisphere of our brain over the other.

The difference between the two hemispheres of the brain – the right hemisphere and the left hemisphere – has been a topic of study for generations. Discussions about the similarities and differences between the brain’s two hemispheres is not new. Iain McGilchrist, a researcher in neuroimaging at Johns Hopkins University, says that comparing the two hemispheres of the brain is like comparing a Mac computer with a PC; there are far more similarities than there are differences. Similarly, both hemispheres of our brains seem to be involved in most everything we do; however, McGilchrist also shows one critical difference; the hemispheres specialize in different functions.

In simple terms, the right hemisphere receives new input from one’s environment while the left hemisphere is supposed to receive that input and create logical categories that make sense out of life. The two hemispheres are intended to function in a back and forth “reverberative” fashion. In other words, as the left hemisphere is creating logical categories based on the data it receives, the right hemisphere continues to provide further real-time input through our sensory experiences that continually adjusts the left hemisphere’s categories. The brain functions at its best when the two hemispheres are collaborating and cooperating. Without the left hemisphere, we could live like animals without being able to pause and ponder. Without the right hemisphere, we can become detached from the real world around us.

In his book The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the West he says that all previous societies started with experience (a right hemisphere function), then moved to abstract reasoning (a left hemisphere function). However, Descartes and the Enlightenment—or what is called modernity—shifted the starting point.

Despite all their contributions, Enlightenment scholars had a preference for rational thinking (left hemisphere) and were suspicious of experience (right hemisphere), the world of story and metaphor. Modernists put excessive emphasis on rationality – concepts and abstract theory as opposed to story, so the West eventually became a lead-with-the left culture.

According to McGilchrist, that’s a problem. The left hemisphere often overshadows the right hemisphere because it’s the hemisphere of language, so it operates with sophisticated language and concepts. Ultimately, the left can say to the right, “Who needs you?” This rational, analytical left hemisphere of our brain becomes a bully.

And here is the even bigger dilemma; It is only in the “right brain” that we experience the world as it truly is. This is the world of stories and images and music that electrify our senses with fresh input. The left explains experience, creating meaningful categories from the real world. But acting on its own, the left hemisphere becomes unaware. Cut off from the right hemisphere and fresh experiences, the left learns nothing new. It just keeps recycling old information. The problem becomes acute when a lead-with-the-left society becomes trapped in the left-hemisphere world.

The good news in our Post-Enlightenment society – at least to those who know to harness its power – is resurgence of the use of story (lead with the right) as story is being implemented in profound ways to impact how people think, what they believe, and how they behave. Here are a couple of examples:

Examples of the Power of Storytelling

In 1988, Jay Winsten was a professor at Harvard. That year he was visiting Scandinavian countries where he learned about a prevalent norm called “the designated driver.” In 1988 this norm did not exist in the United States.

Nobody on this side of the pond even knew what a designated driver was. Winsten returned to the US, inspired about the potential of this program to save thousands of lives. In 1991, just three years after Winsten launched his “Designated Driver” campaign, 90 percent of Americans were familiar with the term. Of those polled, 37 percent said they had acted as a designated driver, and 54 percent of frequent drinkers indicated that they had been driven home by a designated driver. How did Winsten do that? What was his secret?

Winsten did not start by writing a reasoned treatise on the perils of drunk driving. He did not debate with senators to enact new laws. Rather, Winsten seeded this new idea by collaborating with Hollywood. He met with producers, actors, and writers from more than 160 prime-time TV programs to naturally insert designated-driver moments into plots. He always requested “just five seconds” of dialogue featuring the designated-driver idea.

Segments featuring the designated driver appeared on shows like Mr. Belvedere and Who’s the Boss. A designated-driver poster also appeared on Cheers. In one episode of the 1990s series LA Law, the show’s star asked the bartender to call his designated driver.

Winsten’s strategy paid off. The behavior contagion among Americans to designate drivers was credited for a decrease of alcohol-related traffic fatalities from 24,000 in 1988 to 18,000 in 1992—a 25 percent reduction in just three years, and it was accomplished through story.

Around the same time Jay Winsten was launching his Designated Driver campaign, another movement was described in a book published in 1989 by Marshall Kirk and Hunter Madsen entitled After the Ball: How America Will Conquer its Fear and Hatred of Gays in the 90’s. This movement had actually been underway since the 70s to change the perception of homosexuality in our culture. If you reflect back on the public image of same-sex relationships 40 years ago, it was generally negative.

Compare that image to current America: gays are typically viewed as professional, sophisticated, educated, cultural elites. How did this seismic shift in perception happen from predominantly negative to overwhelmingly positive public perception happen in the span of one generation? Regardless of your politics or your personal stance on same-sex relationships, their strategy was undeniably brilliant. Kirk and Madsen chronicle that the gay community embarked on a massive media campaign to change the narrative. Specifically, they sent their brightest and best to Hollywood and Broadway. By telling excellent stories on the big screen and the small screen and on stage, they changed stereotypes and neutralized anti-gay prejudice.

Winning the Story Wars

Jonah Sachs wrote a book in 2013 entitled Winning the Story Wars. He subtitled it “Why Those Who Tell – and Live – the Best Stories will Rule the Future. While Hollywood is winning over the culture by telling good stories, other efforts to shape minds and hearts with reason and logic alone is akin to holding back the ocean’s tide with a plastic bucket and toy shovel. It is not enough that our reason and logic be correct and true. The succeeding generations need more than concepts and abstract theory. They need alternate images embedded by story to form their deepest convictions and to shape their lives.

Using story to develop leaders

(Michelle:) We thought it would be helpful to give you a taste of how we use story to develop leaders. A session in one of our modules focuses on one of the great challenges of leaders: finishing well. We use the following story entitled The Shadow of a Leader to teach this important principle. Listen as I tell the story. Afterward I’ll ask a few questions:

The employees listened carefully as the meeting began. An announcement had been scheduled to recognize Frank Bowman’s thirty years as CEO of Western HD. Frank had recently been appointed as the parent company Smithco’s next CEO.

Frank deserved accolades in many ways. He had grown up with a father who gave little affirmation but much punishment. His childhood was one of loneliness and rejection. So when he became an adult, he was driven to make a difference. Frank had been a young, gifted tour de force. In the early years, Frank had been a consistent voice for integrity and humility in Western HD. He had led the company to develop a variety of cutting-edge products, which minimized invasive surgical techniques and postoperative pain .

Everyone rose to their feet as Frank was announced as the new CEO of Smithco’s. The board chair charged everyone to follow in the shadow of this exceptional leader!

None of those assembled would disagree with the impact of Frank’s career. But one person was overheard to say, “If Western HD is his shadow, then Smithco is in trouble.”

Looking back, few would say that “Frank,” as everyone called him when he started Western HD in 1988, was the same person who was on the platform in 2018. Matt and Sarah, two of the only remaining employees from those early years at Western HD, left the program that day and talked about how Frank and Western HD had changed.

The first years were exciting. Frank kept an open-door policy. He encouraged employees to drop-in. He inspired innovation among others through both his vision and encouragement. As a team player, he welcomed others’ input. All this proved essential in the growth of the company.

But slowly Frank’s leadership approach began to change. It didn’t happen suddenly, but little by little the close working relationships he had always had with the employees became less, especially with Matt and Sarah.

As Western HD grew, he was invited to travel and consult and, in the process, became a sought-after speaker. It wasn’t long, however, before the early signs of “big boss sickness” began to appear. At first, no one seemed to notice. There was no objection when Frank took several sizable raises as well as pocketing all the fees from his consulting services. After all, this is common among business owners, as was the perk of a Tesla Model S. Matt and Sarah could not help remembering, however, that Frank had previously been critical of leaders who spent lavishly on themselves rather than sharing the company’s profits with employees.

Also, no one seemed to think it strange when Frank spent little time with his employees. As pressure on his time increased, spontaneous get-togethers gave way to weekly mandatory staff meetings, always led by Frank, who was now called “Mr. Bowman.” The difficulty of seeing Mr. Bowman without scheduling an appointment because of his new closed-door policy should have been a danger sign.

As Matt and Sarah discussed the past, they also saw how Mr. Bowman had eventually taken control of every aspect of the business. He insisted on making nearly every decision and approving every financial expenditure. This created a bottleneck that resulted in delays and lost opportunities.

Instead of encouraging new ideas and initiatives, Mr. Bowman no longer tolerated deviation from his directives. Those offering a differing opinion suffered in many ways, ranging from being humiliated to being fired from their position.

Revenue still looked good, but morale began to decay in most departments of Western HD. Promising younger workers left hoping to find work that offered more purpose and support. It was then that Matt and Sarah realized that their friend and colleague had fallen guilty to misusing the power of his position. It had become a means solely for self- advancement.

Question 1: What do we know about Frank’s early years as CEO of Western HD?

Question 2: Would you say Frank started out well?

Question 3: How would you describe Frank’s later leadership?

Question 4: What are some possible explanations for Frank’s change in behavior?

(Rick:) To go deeper into the rabbit hole, pick up the book Leading with Story

Leave a Reply