Ordering a search of “leadership development” from Google currently yields 29 million menu options. Both for-profit and not-for-profit organizations invest billions of dollars each year on strategies intended to develop leaders. The pervasive need for better leaders in all spheres of private and public life teases our appetite for solutions.

But has all our investment of time, energy, and money paid off? What is the “return on investment (ROI)” for developing leaders? Do our efforts to develop leaders really work? And if so, what kind of leadership development works? I grappled with these questions for many years. Hopefully this article contributes to the discussion.

As a starting point, I share a part of my own development as a leader – it started with a colossal disruption.

During seminary, I was eager to prove just how much I had learned in my theology and ministry classes. I couldn’t wait until graduation to begin preaching. So in my second year of seminary I convinced a small rural church that they needed me as their weekend pastor. They succumbed, and I began with great expectations. Every Sunday, I delivered my biblical treatises sprinkled with sufficient references to Hebrew and Greek. I was very proud of my sermons. But they weren’t impressed. And the congregation dwindled. In retrospect I realize that I was preaching, but not communicating; talking, but not listening; driving, but not leading.

During my second year as pastor, the people of the church decided to host a revival – without telling me. They invited an evangelist for their special series of meetings. The evangelist was uneducated and unsophisticated, but he attracted record numbers to the services. Some of the most resistant made decisions to follow Christ. The revival was the talk of their small town, and it extended from one week to three.

The revival was humiliating for me. At the end of the revival, I resigned. And the evangelist became their pastor. Under his leadership during the next few years, the church grew steadily. I learned an important lesson: dispensing knowledge is not the same as leading well. I deeply value my seminary education, but it was inadequate in itself to develop me as a leader.

This church experience made me reluctant to enter church ministry. My wife and I had decided that we would pursue another career path after completing our studies. However, two weeks before graduation day, a pastor named David Muir phoned me from Pennsylvania. He needed an assistant pastor.

I responded, “Thank you, but I’m NOT interested.”

He insisted, “Why don’t you just come to visit for the weekend? ”

So I went for a visit. As soon as we met, I realized that this pastor and I were very different. But that weekend he said to me, “I know you’ve been through a tough experience, and you seem teachable now. If you’ll come to be the assistant pastor, it won’t be for what you can do for this church, but we want you to come for what we can do for you.” That was like music to my ears. So for the next few years, I served as his assistant while he poured his life into me. He shared wisdom and life lessons, and he believed in me. And it profoundly changed me. My life’s passion to develop leaders is a debt of love and gratitude to this one who invested in me.

David Muir never studied leadership. He never called what he did “leadership development” or “mentoring.” But he was very effective. He knew that the outcome of authentic Christ-centered leadership is life transformation. David did not use me to benefit his church; rather, he prepared me to my highest potential to serve others. Combined with the years of seminary training, David’s relational investment changed my life.

The Research

Following my mentoring experience with David Muir, I have held various ministry roles, years that included teaching in a seminary and pastoring a local church. During those years, my interest and participation in developing leaders grew steadily. But the questions persisted: Does leadership development work? And if so, what works? How do seeds flourish?

With these questions, I entered a Ph.D. program in Organizational Leadership at Regent University. After the course work was completed, my dissertation project afforded the opportunity to address the questions.

To understand the background of the dissertation project, it is necessary here to explain the definitions and methods used in the research project.

Contributors to a Leader’s Emergence

First, there was a need to differentiate between leadership emergence and leadership development. In addition to intentional leadership development efforts for adults, there are inherent and environmental factors that will enable (or disable) the potential of an individual to be an effective leader.

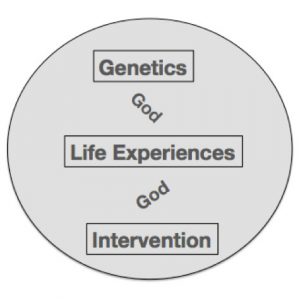

Three elements are to be considered in a leader’s emergence:

- genetics: one’s hard wiring from birth

- life experiences: especially those experiences of childhood, puberty, and adolescence

- intervention: what we have typically called “leadership development”

Therefore, leadership development is actually a subset of leadership emergence.

In view of the broader topic of leadership emergence, I defined leadership development as “adult-focused interventions that are intended to intervene, alter, create, enhance, and/or accelerate effective leadership practices.”

From the Judeo-Christian perspective, God superintends the emergence of leaders. Each new generation requires a new community of leaders. And God – not the interventionist – is the ultimate leadership developer. This view provides perspective and humility as we seek to be instruments of change while recognizing our limitations in the lives of leaders.

Second, I needed to categorize the multifaceted types of leadership development available today. For this I went to the Center for Creative Leadership for their classifications.

The categories of leadership development are as follows:

- Multi-rater feedback – more popularly referred to as 360-degree feedback, this type gathers information from multiple sources related to the leader (supervisor, direct reports, coworkers, etc.) and provides evaluation.

- Skill-based training – the participant engages in a formal or non-formal structured event (ranging from one day to multi-year) that focuses on a preferred or multiple competencies.

- Feedback-intensive program – similar to skill-based training, but with intensive personal feedback that focuses more on the whole person rather than skills alone.

- Developmental job assignment – a new assignment (or new task within an existing assignment) that stretches the participant beyond his/her former set of competencies, relationships, or structures.

- Developmental relationship – more commonly referred to as coaching or mentoring, this type emphasizes life-on-life modeling and teaching, and tends to be more informal.

Third, a valid, reliable empirical method was needed to determine if any of the five leadership development types are effective. And if so, which type – or combination of types – is more effective than others? To this end a research tool called “self-typing paragraphs” was employed in the methodology. I crafted ten paragraphs representing two facets of the five leadership development types. The first paragraph in each set described someone who had experienced that type; the second paragraph described someone who had not experienced that type of leadership development.

Fourth, a means to evaluate a leader’s effectiveness was critical to validate the research. For this aspect of the methodology, I selected Kouzes and Posner’s Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI).

The five exemplary leadership practices evaluated by the LPI are:

- challenging the process

- inspiring a shared vision

- enabling others to act

- modeling the way

- encouraging the heart

One-hundred senior and mid-level leaders from Asia, Africa, Europe, North America, and South America participated in the study. Each was provided with a packet containing the ten self-typing paragraphs and was instructed to identify those paragraphs that most closely described their leadership development experience – or lack of it. They were asked to respond “yes” to one paragraph and “no” to one paragraph in each of the five sets.

Then each leader was evaluated by a minimum of five individuals (self, supervisor, one direct report, two coworkers) using the LPI.

The scores across the five exemplary leadership practices encompassed by the LPI, along with each leader’s responses to the self-typing paragraphs were statistically evaluated by SPSS software. Comparison were observed between the scores of leaders who had experienced no leadership development, one leadership development experience, or a combination of leadership development experiences with other leaders who had different experiences or sets of experiences. Patterns and variations revealed types of leadership development – or combinations of types –that result in positive change in a leader’s behavior.

The research yielded several very significant conclusions:

- Training by itself is not effective. Those individuals who had experienced training only demonstrated no significant positive change in their leadership behavior. The study revealed that training is beneficial to enhance a group’s sense of common language, to define the ideal (what ought to be), and to reveal the gap between the ideal state and the participant’s current state (what is). But training is almost never effective by itself to close the gap between the leader’s ideal and current state.Moreover, training as a stand-alone is often perceived as counterproductive by the leader’s associates. This is due to the fact that training tends to increase the expectations among the leader’s coworkers. But when no observable behavioral change follows the training, the gap increases between expectations and reality. In addition, leaders who participate in competency training with no evident leadership behavior change tend to resist future learning opportunities in those same competencies, thus creating a barrier to behavior change.This conclusion serves as a major caution since approximately 95% of all current leadership development efforts are categorized as stand-alone training

- Mentoring (Developmental Relationships) by itself is not significantly effective. Although mentoring is perceived as beneficial by the mentor and the mentee, it is not perceived as a significant factor for actual positive leadership behavior change by the leader’s direct reports and coworkers. The study indicates that mentoring must be combined with other leadership development types for significant effectiveness.

- Developmental Job Assignments is the only type of leadership development that yielded moderately positive results as a stand-alone. In other words, if one type of leadership development was ranked above all others, the hard knocks of real experience results in the most significant leadership behavior change. Nevertheless, the research revealed that no type of leadership development by itself results in highly significant behavior change in a leader.

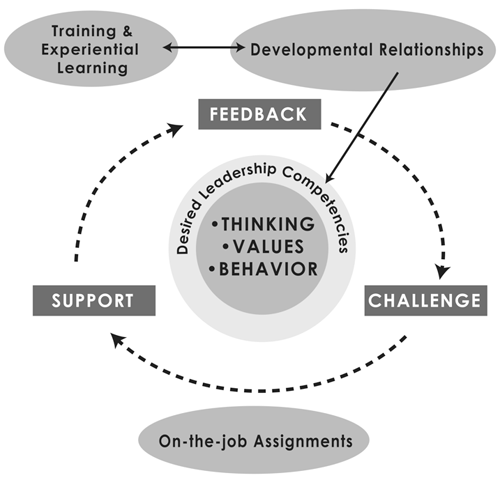

- The most effective approach to developing leaders is to combine three types: Training, Mentoring, and Developmental job assignments. A strategy that prioritizes intermittent training events combined with mentoring (containing the elements of ongoing assessment, challenge, and support) that occurs “on-the-job” yields the most satisfying results in changed leadership behavior.

Some implications from the graph above include:

- The line from “training” to “desired leadership competencies” flows through “mentoring.” This finding suggests that mentoring is essential to foster significant observable change in the leader.

- The line between “training” and “coaching” flows both ways. This suggests that effective training and mentoring should be integrated. Therefore, mentoring and training should be synchronized as one includes the other.

- The process of developing desired leadership traits requires ongoing mentoring that provides:

- assessment: helping the leader assess his/her leadership growth progress.

- challenge: encourage risk, abandon comfort zones, explore areas of potential growth.

- support: providing presence and support systems to avoid discouragement and assurance that the goals are worthy of the participant’s effort.

Conclusions

Based on my life and learning, what are the implications for those of us who are committed to develop Christ-centered leaders?

- We must prioritize mentoring alongside training in our matrix of leadership development strategies. Younger leaders worldwide are expressing a need for mentoring. Organizations are increasingly convinced that mentoring is critical for developing effective leaders. Training by itself will not suffice; leadership models that demonstrate both training and mentoring are the future.

- We need to face the reality that our dominant strategies for leadership development – training events that are sporadically supplemented by follow-up – are often counterproductive. Continuing to rely on this strategy will do little to help – and maybe even harm – our well-intentioned efforts to bring positive change in leaders.

- We have to focus on developing mentors who understand and apply the need for ongoing assessment, challenge, and support through mentoring for the leader. All three are crucial; the absence of even one of these elements will inhibit the leader’s growth.

- Every level of leadership needs to invest seriously in real-time, real-life mentoring. Although training events – even with competent trainers- tend to be popular, the overwhelming evidence demonstrates that transformation occurs when mentoring is featured and championed as part of an organization’s development strategy.

We have to face the fact that, despite our best and most sincere efforts, even the most trustworthy process will fail sometimes. Occasionally losing face is no reason to lose faith. In fact, disruptions increase the potential for positive change. My initial failure as a pastor made me ripe for incredible transformation in the hands of a committed mentor who modeled the two-way relationship. As developers of leaders, we also take risks, moving into new territories of transparent relationship.

The evidence I’ve gleaned from ministry experience and in the classroom has converged on a singular conviction regarding leadership development: intermittent training and ongoing mentoring a leader as he/she works out life and leadership realities on the job is the most reliable means of affecting positive change. The heart cry from around the world, from leaders at every level is for mentors who will walk alongside them in a relational role of modeling and teaching.

As a Christian leader, my ultimate model is Jesus. He purposely entered this wounded world. He pioneered a path to multiply leaders who shared His compassion and His commitment. He chose a small group of individuals into whom He invested. He didn’t do everything; He did specific things. He lived in real time, between the now and the not yet with the cloak of divine eternity lain aside, experiencing the limitations of a human to affect the lives of others. Yet He was ultimately Messiah Who completed His work and embodied the Kingdom.

Even as we follow His example and teachings, we have to square it with the reality expressed by Oscar Romero, the martyred archbishop from El Salvador who wrote:

“We cannot do everything, and there is a sense of liberation in that. This enables us to do something and to do it well. It may be incomplete but it is a beginning, a step along the way…We may never see the end results, but that is the difference between the master builder and the worker. We are workers, not master builders; ministers not messiahs. We are prophets of a future not our own.”

Rick Sessoms

November 2008

Download PDF of My Journey Toward Understanding Leadership Development